Fieldwork at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Interdisciplinary Approaches to Museum Education for the Blind

By Sue Mengchen XuInterdisciplinary Approaches to Museum Education for the Blind or Partially Sighted: Fieldwork at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Good afternoon everyone, my name is Sue. I’m an art educator, advisor and writer based in Beijing.

When we step into a museum, the first sensory system we begin to activate is our eyes. By looking closely, whether at the objects themselves or their wall labels, we enjoy and learn about art. If we rely so heavily on vision when we visit an art museum, can we imagine an experience without it? Growing up with a family member with a physical disability, I’ve always been aware of the visible and invisible barriers our society has placed on certain resources that many of us take for granted. For visitors who are blind or visually impaired, for example, the experience of visiting a museum and enjoying art can simply be unimaginable.

Comparing to other public institutions, museums are imbedded with an extra layer of difficulty because the interpretation of art is often a barrier on its own. That’s why we have educators who give gallery talks, record audio guides, and provide other assistive materials to make the thoughts and context behind art accessible and understandable. But have we done enough? For those of us sitting in this room or tuning in online, we’ve come a long way to not only feel at ease at an art museum, but also dare to partake in its future. Now, instead of marching forward, I’d like us to take a step back and look at our society at large. Who’s not around, and who’s left behind? If art is a universal language, have we given enough access to the artworks in our museums so they can truly speak to all? In my presentation today, I’ll use the access programs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, also known as the Met, as a case study to introduce the general practices in the field and the value of cross- community dialogues.

As the largest art museum in the US, the Met has a long history of making art accessible to people who are blind or partially sighted. One of the museum’s most popular programs for the blind is touch tours. During these tours, original works of art are carefully chosen by the museum’s conservation and education professionals for the purpose of tour tours so blind visitors can trace their contours and experience their tactile qualities including form, scale, texture, and temperature.

Touch tours at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, image from the Met | © Arts Access

Another common program in the field of museum accessibility for the blind is verbal imaging, also known as visual description. Those who have gone through an art history curriculum might be familiar with the termbecause it’s usually our first assignment when we approach the writing of art. It brings our attention to the compositional elements of an artwork such as color, line, shape, and other perceptual aspects, before we go into theiconography or the historical and social context. Those who are museum educators might also find this method relatable, because one of the most widely used pedagogies in art museums called Visual Thinking Strategies or VTS is also rooted in the act of close looking and the extensive description of visual details.

Touch tours at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, image from the Met | © Arts Access

Another common program in the field of museum accessibility for the blind is verbal imaging, also known as visual description. Those who have gone through an art history curriculum might be familiar with the termbecause it’s usually our first assignment when we approach the writing of art. It brings our attention to the compositional elements of an artwork such as color, line, shape, and other perceptual aspects, before we go into theiconography or the historical and social context. Those who are museum educators might also find this method relatable, because one of the most widely used pedagogies in art museums called Visual Thinking Strategies or VTS is also rooted in the act of close looking and the extensive description of visual details.

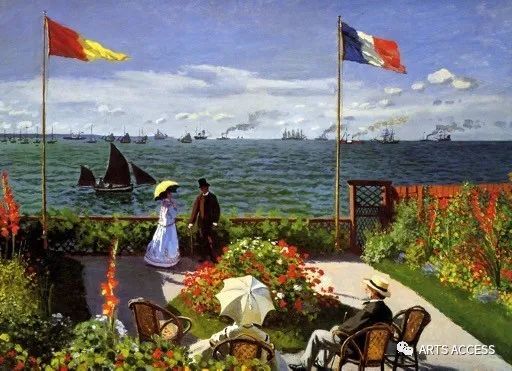

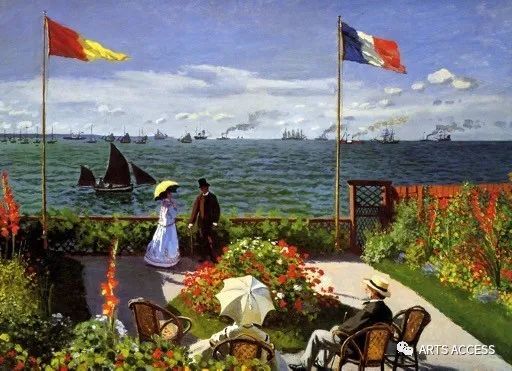

How is the visual description for the blind different from the one we all know? What more can we provide besides the information that’s already in place? To give you an example, let’s look at Monet’s Garden at Sainte-Adresse in the Met’s collection.

Claude Monet, Garden at Sainte-Adresse, 1867, imag from the Met | © Arts Access

To introduce this work to a blind visitor, the first step is to properly orient ourselves and let your audience know exactly where we are in spatial terms and how we got here. In the case of this Monet painting, it’s on the second floor of the museum. If you walk in from the corridor of Canter Sculpture Gallery, you will find the painting on your left-hand side, hanging in the center of the wall.

Claude Monet, Garden at Sainte-Adresse, 1867, imag from the Met | © Arts Access

To introduce this work to a blind visitor, the first step is to properly orient ourselves and let your audience know exactly where we are in spatial terms and how we got here. In the case of this Monet painting, it’s on the second floor of the museum. If you walk in from the corridor of Canter Sculpture Gallery, you will find the painting on your left-hand side, hanging in the center of the wall.

The second step is to introduce the environment. In the room where this painting is hung, the walls are painted in creamy white, and the floor is covered by light-brown hard wood with a beam of sunlight pouring through the glass ceiling.

This is when things start to get tricky: to someone who has never experienced vision, what is light? And what is shadow? We use these terms on a daily basis but rarely consider what they actually entail. In this case, can we bring in other sensory experiences just like how we did in touch tours in describing light and shadow? I found a number of answers in my research, and here is my favorite: To describe light, imagine you’re sit infront of a window on a sunny day, light the warmth you feel on your body. Shadow is when you stand in the shower, imagine the water coming down from the shower head as a light source, the front of your body that gets wet is the highlight, and the back of your body that’s still dry is the shadow.

During my internship at the Met in 2014, I worked under the Education Department in developing descriptive audio guides in collaboration with Emilie Gossiaux, a fellow intern who is blind. Based on my initial description of an artwork, Emilie provided feedback on the details she wished to hear more and the sequence she preferred them to be told. As an example, I’ll read a short paragraph from the audio guide stop we wrote together:

It’s a clear summer day. You are standing on the second floor of a beach house. When you look out from the porch, you’ll find a patio garden, flourishing with red, white, yellow and orange nasturtium and some red gladioli. On the side of the patio closer to you, there are four wicker chairs, surrounding a rounded cluster of flowers. Only the two chairs in the center are taken. A man with gray beard sits on the right. He is wearing a dark gray jacket and light gray pants, with a white panama hat on his head. He also has a brown cane leaning against his leg. On his left sits a woman, facing the water with her back towards us. She wears a soft white dress, with a white parasol covering her head.

My colleague Emilie Gossiaux and her guild gods in front of the artwork | © Arts Access

My purpose here today is not to teach you any techniques or even raise awareness, because as a participant of Museum 2050, I’m sure we can all agree on the necessity of inclusion and the social responsibility of art. The purpose of this presentation is to show you what’s possible, to let you know that there is a whole community of advocates dedicated in this field and a whole set of pedagogy they’re actively using and developing. Even if you don’t have the capacity to go back to your institution after this conference and immediately establish a program to serve people with disabilities, we can at least reexamine our own lives and the ways in which we engage with art. When the opportunity arises, we can be better prepared to make changes.

My colleague Emilie Gossiaux and her guild gods in front of the artwork | © Arts Access

My purpose here today is not to teach you any techniques or even raise awareness, because as a participant of Museum 2050, I’m sure we can all agree on the necessity of inclusion and the social responsibility of art. The purpose of this presentation is to show you what’s possible, to let you know that there is a whole community of advocates dedicated in this field and a whole set of pedagogy they’re actively using and developing. Even if you don’t have the capacity to go back to your institution after this conference and immediately establish a program to serve people with disabilities, we can at least reexamine our own lives and the ways in which we engage with art. When the opportunity arises, we can be better prepared to make changes.

Thank you very much.

When we step into a museum, the first sensory system we begin to activate is our eyes. By looking closely, whether at the objects themselves or their wall labels, we enjoy and learn about art. If we rely so heavily on vision when we visit an art museum, can we imagine an experience without it? Growing up with a family member with a physical disability, I’ve always been aware of the visible and invisible barriers our society has placed on certain resources that many of us take for granted. For visitors who are blind or visually impaired, for example, the experience of visiting a museum and enjoying art can simply be unimaginable.

Comparing to other public institutions, museums are imbedded with an extra layer of difficulty because the interpretation of art is often a barrier on its own. That’s why we have educators who give gallery talks, record audio guides, and provide other assistive materials to make the thoughts and context behind art accessible and understandable. But have we done enough? For those of us sitting in this room or tuning in online, we’ve come a long way to not only feel at ease at an art museum, but also dare to partake in its future. Now, instead of marching forward, I’d like us to take a step back and look at our society at large. Who’s not around, and who’s left behind? If art is a universal language, have we given enough access to the artworks in our museums so they can truly speak to all? In my presentation today, I’ll use the access programs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, also known as the Met, as a case study to introduce the general practices in the field and the value of cross- community dialogues.

As the largest art museum in the US, the Met has a long history of making art accessible to people who are blind or partially sighted. One of the museum’s most popular programs for the blind is touch tours. During these tours, original works of art are carefully chosen by the museum’s conservation and education professionals for the purpose of tour tours so blind visitors can trace their contours and experience their tactile qualities including form, scale, texture, and temperature.

Touch tours at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, image from the Met | © Arts Access

Touch tours at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, image from the Met | © Arts Access

How is the visual description for the blind different from the one we all know? What more can we provide besides the information that’s already in place? To give you an example, let’s look at Monet’s Garden at Sainte-Adresse in the Met’s collection.

Claude Monet, Garden at Sainte-Adresse, 1867, imag from the Met | © Arts Access

Claude Monet, Garden at Sainte-Adresse, 1867, imag from the Met | © Arts Access

The second step is to introduce the environment. In the room where this painting is hung, the walls are painted in creamy white, and the floor is covered by light-brown hard wood with a beam of sunlight pouring through the glass ceiling.

This is when things start to get tricky: to someone who has never experienced vision, what is light? And what is shadow? We use these terms on a daily basis but rarely consider what they actually entail. In this case, can we bring in other sensory experiences just like how we did in touch tours in describing light and shadow? I found a number of answers in my research, and here is my favorite: To describe light, imagine you’re sit infront of a window on a sunny day, light the warmth you feel on your body. Shadow is when you stand in the shower, imagine the water coming down from the shower head as a light source, the front of your body that gets wet is the highlight, and the back of your body that’s still dry is the shadow.

During my internship at the Met in 2014, I worked under the Education Department in developing descriptive audio guides in collaboration with Emilie Gossiaux, a fellow intern who is blind. Based on my initial description of an artwork, Emilie provided feedback on the details she wished to hear more and the sequence she preferred them to be told. As an example, I’ll read a short paragraph from the audio guide stop we wrote together:

It’s a clear summer day. You are standing on the second floor of a beach house. When you look out from the porch, you’ll find a patio garden, flourishing with red, white, yellow and orange nasturtium and some red gladioli. On the side of the patio closer to you, there are four wicker chairs, surrounding a rounded cluster of flowers. Only the two chairs in the center are taken. A man with gray beard sits on the right. He is wearing a dark gray jacket and light gray pants, with a white panama hat on his head. He also has a brown cane leaning against his leg. On his left sits a woman, facing the water with her back towards us. She wears a soft white dress, with a white parasol covering her head.

My colleague Emilie Gossiaux and her guild gods in front of the artwork | © Arts Access

My colleague Emilie Gossiaux and her guild gods in front of the artwork | © Arts Access

Thank you very much.