Disability Arts Gather Momentum in China

By Lisa Movius“When we perform, some people ask, ‘Why even come out in public? Why bother, when the government takes care of you?’”

“When we perform, some people ask, ‘Why even come out in public? Why bother, when the government takes care of you?’ This kind of sound,” describes Liu Shiwen, a dancer and choreographer for Guangzhou’s Mistakable Symbiotic Dance Troupe. Symbiotic, established in 2018, presents contemporary dance created and performed by people with disabilities. Liu says most audiences are supportive if a bit condescending, “worried we will hurt ourselves,” but others, “feel that we don’t have any social value, that we are lazy and useless. But then, when we dance, they are moved, and realise we are powerful and hopeful.” Their performances, such as 2020’s Is My Body My Master?, evidence the beauty as inherent to atypical bodies as any sort of human. Liu supposes that many in China believe that art is a luxury or a frivolity, but for her cohort of dancers with disabilities, as well as their audiences, it is transforming. “Life and the body are important, as is to find out what is possible for you.”

Symbiotic Dance Troupe's performances are choreographed and performed by artists with disabilities. | © Symbiotic Dance Troupe

Symbiotic Dance Troupe's performances are choreographed and performed by artists with disabilities. | © Symbiotic Dance Troupe

The arts can default exclusionary, with even their very definitions specific to senses and capacities. While emotions like love, fear, empathy and insecurity are human universals, vision, sound and fluidity of movement are not. In China, many artistic forms are still in their relatively early stages, with considerations of inclusion and accessibility nascent at best – especially as creatives and institutions struggle to stay afloat in the time of Covid-19. However more and more artists, curators, dance groups and volunteers are working to normalise the breadth of human experience through artistic expression. Disability arts – art by, for and about people with disabilities – are expanding in scope and visibility in China, fomented by performances like Symbiotic’s, or a 2020 exhibition The Same Eyes: Art Sharing Project for the Visually Impaired at the Guangdong Museum of Art.

Symbiotic Dance Troupe's performances are choreographed and performed by artists with disabilities. | © Symbiotic Dance Troupe

Symbiotic Dance Troupe's performances are choreographed and performed by artists with disabilities. | © Symbiotic Dance Troupe

Disability arts in China are by necessity grassroots, scattered and localised, serving specific communities and requirements. A dancer in a wheelchair has different concerns than a blind artist or deaf theatre-goer. China like most countries outlines a legal definition of disability as impeding mental or physical impairments, includes physical, sensory, cognitive, developmental, intellectual and mental conditions as well as their combinations. Some parameters extend to chronic illness as well. China’s 2010 census reported 85 million Chinese nationals recognised as having disabilities, 25 million deemed serious; but several times that likely have unregistered disabilities, and most people will at some point in their lives encounter temporary or permanent forms of impairment due to injury, illness and aging. True to its name, the Diverse As We Are (DAWA) Festival includes an expansive concept of diversity, exploring mental illness, the autism spectrum and unconventional body types as well as what is popularly recognised as disability.

In contemporary art, the only artist with a visible disability to achieve mainstream fame is pioneering sculptor Ma Desheng, who is partly paralysed from childhood polio. More may have invisible disabilities: clichés of tortured genius notwithstanding, societal stigmas prompt most artists with disabilities who can to keep their conditions private. The uncertain realities of what we can and cannot, do or do not hear is only one level of an exhibition at Shanghai’s Duolun Art Museum about the nature of sound. Art and Signs. Deaf Culture / Hearing Culture (10 September to 9 October) features both deaf and hearing artists experimenting with song, sound and sign language.

“Because we are a public art museum, our exhibitions and events are free and open to the public, and we focus more on how art connects with the public and society,” describes Duolun assistant director Elvis Gu, who co-curated the exhibition with An Paenhuysen and with advisor Alice Hu. “We do some public welfare and artistic exhibitions every year, and last year we did an art exhibition about women,” who also remain underrepresented in China’s contemporary art systems. While gender issues in Chinese art remains a controversial if not taboo subject, a push for greater equity in the past several years has carved out more space for women artists to exhibit and to enter and remain in the art field.

“We think that the artists themselves, as women or deaf people, they want to live and communicate in an equal way,” says Gu. “They simultaneously have a strong desire to express, especially for artistic expression across gender and physical limitations, and they have their own artistic talents. Art is a very effective way to help us understand each other, it can open our eyes beyond the limitations of our cognition. Art is also a bridge to communicate with each other, through art, we can get closer to each other and break down prejudices and barriers.”

The 2020 Guangdong Museum of Art exhibition The Same Eyes: Art Sharing Project for the Visually Impaired similarly brought together blind and seeing artists to explore what its curator Zhang Fen describes as, “how we ‘see’ the unseen and non visual art. The project came to focus on the sensory and functional barriers, and can share art with the disabled groups.” The exhibition built upon the museum’s existing history of non-visual exhibitions including multimedia, experiential, interactive, sound and scent works, but anticipating more blind visitors it upgraded voice guidance and installed Braille keys in the elevator. “Fortunately, the artists were very awesome” in their concepts, says Zhang, and the show proved “a minor trend among the visually impaired community, who had relatively few opportunities to enter art museums before, and hotly discussed the exhibition with friends.”

Governmental social welfare efforts include a number of artistic projects for people with disabilities, from the national China Disabled People's Performing Art Troupe, founded in 1987, to provincial and municipal level groups, and down to community art therapy offerings in both performing and fine arts. Though valuable for their engagement, the disability arts troupes have a side effect of sidelining artists with disabilities from mainstream arts systems and spaces, and creating an impression that they are of lower caliber. “Deliberately highlighting the ‘art of the disabled’,” by emphasising their difference, “is actually exacerbating their marginalisation,” says Zhang Fen. “I hope that people with disabilities and art can be naturally integrated, and I advocate for this way of sensory communication.”

An ability to see, or otherwise experience, those like oneself in arts spaces provides huge impetus to young talents to enter creative fields; and their absence a deterrent. This is as true for people with disabilities as it is for women and racial, sexual and economic minorities. However, simply attending exhibitions and events can be challenging for audiences with disabilities, with accessible facilities an afterthought in even some of the newest museums, theatres and livehouses in first tier cities. Access elevators if installed at all are frequently switched off, with few audio guides, Braille or sign language offered. “To understand [people with disabilities] they need to know us, that something like an elevator or an accessible bathroom is minor to them but everything to us,” says Liu Shiwen. Organisations like Shanghai’s Arts Access and Beijing’s Hongdandan facilitate access to art, literature and cinema.

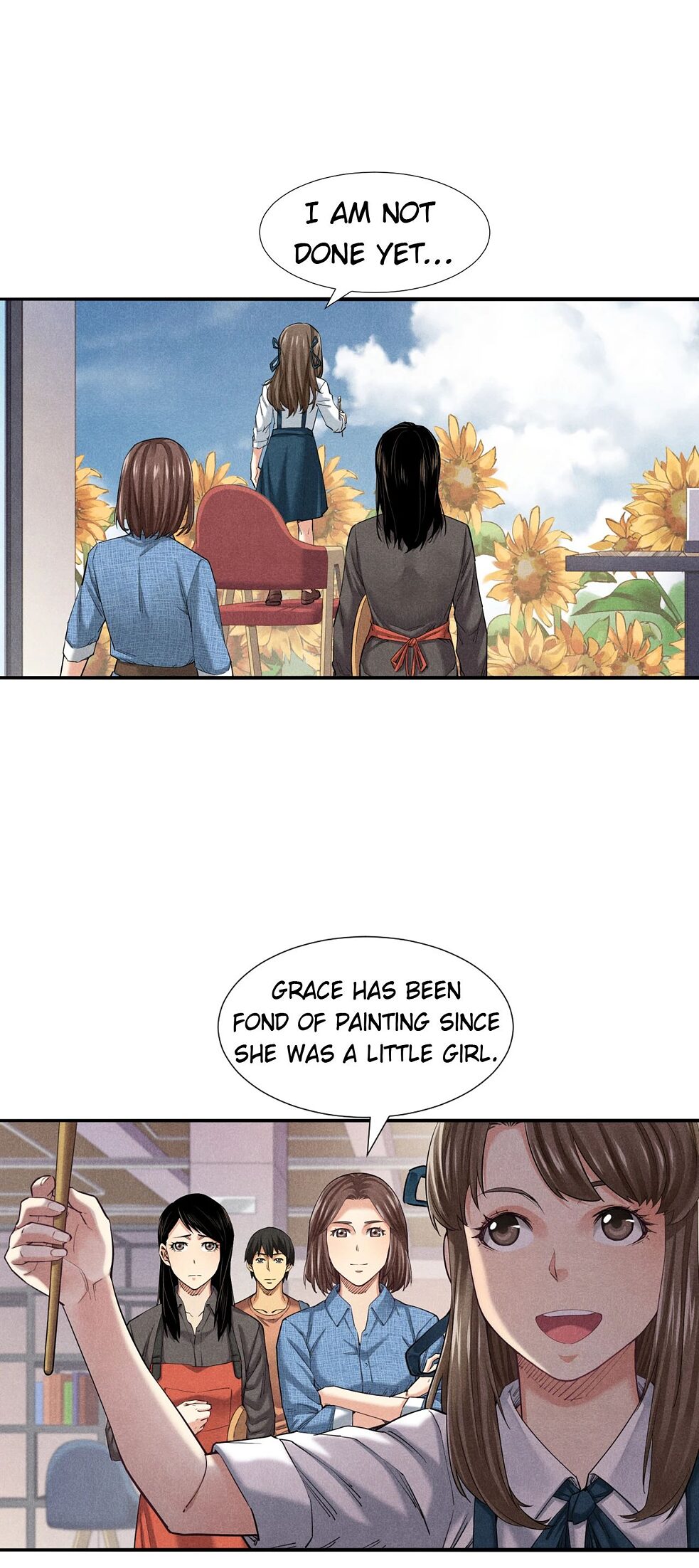

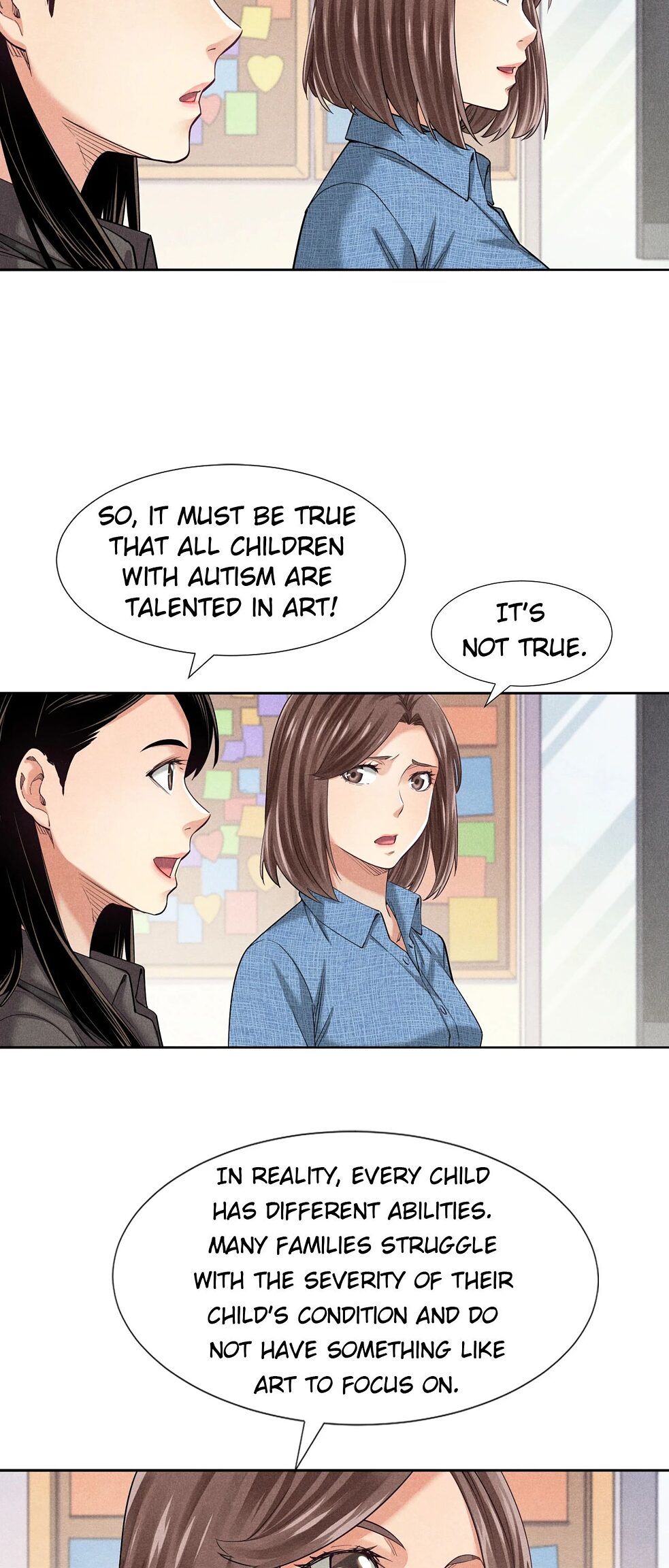

Whether or not created by artists with disabilities themselves, art also can be powerful also to educate the non-disabled population about disability issues, to normalise and integrate them into mainstream conversations. That is the ambition of Xiersen, a nonprofit founded in 2014 and currently producing a manga series Special Slices promoting the “awareness, acceptance and inclusion of special adults,” says its CAO Eva Cheung. Over the years, projects have included autism awareness and highlighting care giving careers like therapists and special educators.

![“When we perform, some people ask, ‘Why even come out in public? Why bother, when the government takes care of you?’ This kind of sound,” describes Liu Shiwen, a dancer and choreographer for Guangzhou’s Mistakable Symbiotic Dance Troupe. Symbiotic, established in 2018, presents contemporary dance created and performed by people with disabilities. Liu says most audiences are supportive if a bit condescending, “worried we will hurt ourselves,” but others, “feel that we don’t have any social value, that we are lazy and useless. But then, when we dance, they are moved, and realise we are powerful and hopeful.” Their performances, such as 2020’s Is My Body My Master?, evidence the beauty as inherent to atypical bodies as any sort of human. Liu supposes that many in China believe that art is a luxury or a frivolity, but for her cohort of dancers with disabilities, as well as their audiences, it is transforming. “Life and the body are important, as is to find out what is possible for you.” The arts can default exclusionary, with even their very definitions specific to senses and capacities. While emotions like love, fear, empathy and insecurity are human universals, vision, sound and fluidity of movement are not. In China, many artistic forms are still in their relatively early stages, with considerations of inclusion and accessibility nascent at best – especially as creatives and institutions struggle to stay afloat in the time of Covid-19. However more and more artists, curators, dance groups and volunteers are working to normalise the breadth of human experience through artistic expression. Disability arts – art by, for and about people with disabilities – are expanding in scope and visibility in China, fomented by performances like Symbiotic’s, or a 2020 exhibition The Same Eyes: Art Sharing Project for the Visually Impaired at the Guangdong Museum of Art. Disability arts in China are by necessity grassroots, scattered and localised, serving specific communities and requirements. A dancer in a wheelchair has different concerns than a blind artist or deaf theatre-goer. China like most countries outlines a legal definition of disability as impeding mental or physical impairments, includes physical, sensory, cognitive, developmental, intellectual and mental conditions as well as their combinations. Some parameters extend to chronic illness as well. China’s 2010 census reported 85 million Chinese nationals recognised as having disabilities, 25 million deemed serious; but several times that likely have unregistered disabilities, and most people will at some point in their lives encounter temporary or permanent forms of impairment due to injury, illness and aging. True to its name, the Diverse As We Are (DAWA) Festival includes an expansive concept of diversity, exploring mental illness, the autism spectrum and unconventional body types as well as what is popularly recognised as disability. In contemporary art, the only artist with a visible disability to achieve mainstream fame is pioneering sculptor Ma Desheng, who is partly paralysed from childhood polio. More may have invisible disabilities: clichés of tortured genius notwithstanding, societal stigmas prompt most artists with disabilities who can to keep their conditions private. The uncertain realities of what we can and cannot, do or do not hear is only one level of an exhibition at Shanghai’s Duolun Art Museum about the nature of sound. Art and Signs. Deaf Culture / Hearing Culture (10 September to 9 October) features both deaf and hearing artists experimenting with song, sound and sign language. “Because we are a public art museum, our exhibitions and events are free and open to the public, and we focus more on how art connects with the public and society,” describes Duolun assistant director Elvis Gu, who co-curated the exhibition with An Paenhuysen and with advisor Alice Hu. “We do some public welfare and artistic exhibitions every year, and last year we did an art exhibition about women,” who also remain underrepresented in China’s contemporary art systems. While gender issues in Chinese art remains a controversial if not taboo subject, a push for greater equity in the past several years has carved out more space for women artists to exhibit and to enter and remain in the art field. “We think that the artists themselves, as women or deaf people, they want to live and communicate in an equal way,” says Gu. “They simultaneously have a strong desire to express, especially for artistic expression across gender and physical limitations, and they have their own artistic talents. Art is a very effective way to help us understand each other, it can open our eyes beyond the limitations of our cognition. Art is also a bridge to communicate with each other, through art, we can get closer to each other and break down prejudices and barriers.” The 2020 Guangdong Museum of Art exhibition The Same Eyes: Art Sharing Project for the Visually Impaired similarly brought together blind and seeing artists to explore what its curator Zhang Fen describes as, “how we ‘see’ the unseen and non visual art. The project came to focus on the sensory and functional barriers, and can share art with the disabled groups.” The exhibition built upon the museum’s existing history of non-visual exhibitions including multimedia, experiential, interactive, sound and scent works, but anticipating more blind visitors it upgraded voice guidance and installed Braille keys in the elevator. “Fortunately, the artists were very awesome” in their concepts, says Zhang, and the show proved “a minor trend among the visually impaired community, who had relatively few opportunities to enter art museums before, and hotly discussed the exhibition with friends.” Governmental social welfare efforts include a number of artistic projects for people with disabilities, from the national China Disabled People's Performing Art Troupe, founded in 1987, to provincial and municipal level groups, and down to community art therapy offerings in both performing and fine arts. Though valuable for their engagement, the disability arts troupes have a side effect of sidelining artists with disabilities from mainstream arts systems and spaces, and creating an impression that they are of lower caliber. “Deliberately highlighting the ‘art of the disabled’,” by emphasising their difference, “is actually exacerbating their marginalisation,” says Zhang Fen. “I hope that people with disabilities and art can be naturally integrated, and I advocate for this way of sensory communication.” An ability to see, or otherwise experience, those like oneself in arts spaces provides huge impetus to young talents to enter creative fields; and their absence a deterrent. This is as true for people with disabilities as it is for women and racial, sexual and economic minorities. However, simply attending exhibitions and events can be challenging for audiences with disabilities, with accessible facilities an afterthought in even some of the newest museums, theatres and livehouses in first tier cities. Access elevators if installed at all are frequently switched off, with few audio guides, Braille or sign language offered. “To understand [people with disabilities] they need to know us, that something like an elevator or an accessible bathroom is minor to them but everything to us,” says Liu Shiwen. Organisations like Shanghai’s Arts Access and Beijing’s Hongdandan facilitate access to art, literature and cinema. Whether or not created by artists with disabilities themselves, art also can be powerful also to educate the non-disabled population about disability issues, to normalise and integrate them into mainstream conversations. That is the ambition of Xiersen, a nonprofit founded in 2014 and currently producing a manga series Special Slices promoting the “awareness, acceptance and inclusion of special adults,” says its CAO Eva Cheung. Over the years, projects have included autism awareness and highlighting care giving careers like therapists and special educators. “We have seen how Special Slices can change people's perceptions and increase compassion,” says Cheung, such as how its creator, manga artist Zhiguo Qu aka Revolver, started out unconnected to the special needs community but found his perspective shifted due to the interaction when preparing their stories. “In China, there are millions of people with intellectual disabilities. According to the Second National Census of the Disabled, the employment rate for intellectually disabled people was less than 2%, the lowest among all disabled groups. For people with ID, working in a supportive environment can make a huge difference in their lives, improving their self-esteem and giving them a sense of purpose.” “The power of manga storytelling has opened up more opportunities for us to connect with inspiring special individuals” and their allies. “It’s a great way to start the conversation about inclusion,” Cheung says, emphasising that still, “a lot more has to be done to create awareness.” “When we perform, some people ask, ‘Why even come out in public? Why bother, when the government takes care of you?’ This kind of sound,” describes Liu Shiwen, a dancer and choreographer for Guangzhou’s Mistakable Symbiotic Dance Troupe. Symbiotic, established in 2018, presents contemporary dance created and performed by people with disabilities. Liu says most audiences are supportive if a bit condescending, “worried we will hurt ourselves,” but others, “feel that we don’t have any social value, that we are lazy and useless. But then, when we dance, they are moved, and realise we are powerful and hopeful.” Their performances, such as 2020’s Is My Body My Master?, evidence the beauty as inherent to atypical bodies as any sort of human. Liu supposes that many in China believe that art is a luxury or a frivolity, but for her cohort of dancers with disabilities, as well as their audiences, it is transforming. “Life and the body are important, as is to find out what is possible for you.” The arts can default exclusionary, with even their very definitions specific to senses and capacities. While emotions like love, fear, empathy and insecurity are human universals, vision, sound and fluidity of movement are not. In China, many artistic forms are still in their relatively early stages, with considerations of inclusion and accessibility nascent at best – especially as creatives and institutions struggle to stay afloat in the time of Covid-19. However more and more artists, curators, dance groups and volunteers are working to normalise the breadth of human experience through artistic expression. Disability arts – art by, for and about people with disabilities – are expanding in scope and visibility in China, fomented by performances like Symbiotic’s, or a 2020 exhibition The Same Eyes: Art Sharing Project for the Visually Impaired at the Guangdong Museum of Art. Disability arts in China are by necessity grassroots, scattered and localised, serving specific communities and requirements. A dancer in a wheelchair has different concerns than a blind artist or deaf theatre-goer. China like most countries outlines a legal definition of disability as impeding mental or physical impairments, includes physical, sensory, cognitive, developmental, intellectual and mental conditions as well as their combinations. Some parameters extend to chronic illness as well. China’s 2010 census reported 85 million Chinese nationals recognised as having disabilities, 25 million deemed serious; but several times that likely have unregistered disabilities, and most people will at some point in their lives encounter temporary or permanent forms of impairment due to injury, illness and aging. True to its name, the Diverse As We Are (DAWA) Festival includes an expansive concept of diversity, exploring mental illness, the autism spectrum and unconventional body types as well as what is popularly recognised as disability. In contemporary art, the only artist with a visible disability to achieve mainstream fame is pioneering sculptor Ma Desheng, who is partly paralysed from childhood polio. More may have invisible disabilities: clichés of tortured genius notwithstanding, societal stigmas prompt most artists with disabilities who can to keep their conditions private. The uncertain realities of what we can and cannot, do or do not hear is only one level of an exhibition at Shanghai’s Duolun Art Museum about the nature of sound. Art and Signs. Deaf Culture / Hearing Culture (10 September to 9 October) features both deaf and hearing artists experimenting with song, sound and sign language. “Because we are a public art museum, our exhibitions and events are free and open to the public, and we focus more on how art connects with the public and society,” describes Duolun assistant director Elvis Gu, who co-curated the exhibition with An Paenhuysen and with advisor Alice Hu. “We do some public welfare and artistic exhibitions every year, and last year we did an art exhibition about women,” who also remain underrepresented in China’s contemporary art systems. While gender issues in Chinese art remains a controversial if not taboo subject, a push for greater equity in the past several years has carved out more space for women artists to exhibit and to enter and remain in the art field. “We think that the artists themselves, as women or deaf people, they want to live and communicate in an equal way,” says Gu. “They simultaneously have a strong desire to express, especially for artistic expression across gender and physical limitations, and they have their own artistic talents. Art is a very effective way to help us understand each other, it can open our eyes beyond the limitations of our cognition. Art is also a bridge to communicate with each other, through art, we can get closer to each other and break down prejudices and barriers.” The 2020 Guangdong Museum of Art exhibition The Same Eyes: Art Sharing Project for the Visually Impaired similarly brought together blind and seeing artists to explore what its curator Zhang Fen describes as, “how we ‘see’ the unseen and non visual art. The project came to focus on the sensory and functional barriers, and can share art with the disabled groups.” The exhibition built upon the museum’s existing history of non-visual exhibitions including multimedia, experiential, interactive, sound and scent works, but anticipating more blind visitors it upgraded voice guidance and installed Braille keys in the elevator. “Fortunately, the artists were very awesome” in their concepts, says Zhang, and the show proved “a minor trend among the visually impaired community, who had relatively few opportunities to enter art museums before, and hotly discussed the exhibition with friends.” Governmental social welfare efforts include a number of artistic projects for people with disabilities, from the national China Disabled People's Performing Art Troupe, founded in 1987, to provincial and municipal level groups, and down to community art therapy offerings in both performing and fine arts. Though valuable for their engagement, the disability arts troupes have a side effect of sidelining artists with disabilities from mainstream arts systems and spaces, and creating an impression that they are of lower caliber. “Deliberately highlighting the ‘art of the disabled’,” by emphasising their difference, “is actually exacerbating their marginalisation,” says Zhang Fen. “I hope that people with disabilities and art can be naturally integrated, and I advocate for this way of sensory communication.” An ability to see, or otherwise experience, those like oneself in arts spaces provides huge impetus to young talents to enter creative fields; and their absence a deterrent. This is as true for people with disabilities as it is for women and racial, sexual and economic minorities. However, simply attending exhibitions and events can be challenging for audiences with disabilities, with accessible facilities an afterthought in even some of the newest museums, theatres and livehouses in first tier cities. Access elevators if installed at all are frequently switched off, with few audio guides, Braille or sign language offered. “To understand [people with disabilities] they need to know us, that something like an elevator or an accessible bathroom is minor to them but everything to us,” says Liu Shiwen. Organisations like Shanghai’s Arts Access and Beijing’s Hongdandan facilitate access to art, literature and cinema. Whether or not created by artists with disabilities themselves, art also can be powerful also to educate the non-disabled population about disability issues, to normalise and integrate them into mainstream conversations. That is the ambition of Xiersen, a nonprofit founded in 2014 and currently producing a manga series Special Slices promoting the “awareness, acceptance and inclusion of special adults,” says its CAO Eva Cheung. Over the years, projects have included autism awareness and highlighting care giving careers like therapists and special educators. “We have seen how Special Slices can change people's perceptions and increase compassion,” says Cheung, such as how its creator, manga artist Zhiguo Qu aka Revolver, started out unconnected to the special needs community but found his perspective shifted due to the interaction when preparing their stories. “In China, there are millions of people with intellectual disabilities. According to the Second National Census of the Disabled, the employment rate for intellectually disabled people was less than 2%, the lowest among all disabled groups. For people with ID, working in a supportive environment can make a huge difference in their lives, improving their self-esteem and giving them a sense of purpose.” “The power of manga storytelling has opened up more opportunities for us to connect with inspiring special individuals” and their allies. “It’s a great way to start the conversation about inclusion,” Cheung says, emphasising that still, “a lot more has to be done to create awareness.”](/resources/files/jpg1189/xiersens-manga-series-special-slices-by-zhiguo-qu-aka-revolver-educates-young-readers-about-the-experiences-of-adults-and-children-with-intellectual-disabilities-their-families-and-their-caregivers_4-formatkey-jpg-w983.jpg) © Zhiguo Qu

© Zhiguo Qu

© Zhiguo Qu

© Zhiguo Qu

© Zhiguo Qu

© Zhiguo Qu

© Zhiguo Qu

© Zhiguo Qu

“We have seen how Special Slices can change people's perceptions and increase compassion,” says Cheung, such as how its creator, manga artist Zhiguo Qu aka Revolver, started out unconnected to the special needs community but found his perspective shifted due to the interaction when preparing their stories. “In China, there are millions of people with intellectual disabilities. According to the Second National Census of the Disabled, the employment rate for intellectually disabled people was less than 2%, the lowest among all disabled groups. For people with ID, working in a supportive environment can make a huge difference in their lives, improving their self-esteem and giving them a sense of purpose.”

“The power of manga storytelling has opened up more opportunities for us to connect with inspiring special individuals” and their allies. “It’s a great way to start the conversation about inclusion,” Cheung says, emphasising that still, “a lot more has to be done to create awareness.”